Waste For Warmth: keeping out the cold with plastic

- Field Ready

- Mar 4, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 6, 2021

It’s still winter in the Northern Hemisphere, and freezing in much of it. Yet more than 6 million displaced people are living in flimsy, inadequately thin temporary shelters across the Middle East and Europe because no better options currently exist. Cold is often their constant companion at this time of year.

Enter Waste For Warmth: For the last year Field Ready has been working with partners Engineers Without Borders Norway, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent’s Shelter Research Unit and The Polyfloss Factory to find ways to use Polyfloss to help keep tented housing warmer. Collaborating for the Human Innovation Programme, the Waste For Warmth project team has spent the past few weeks testing insulated tent panels made from recycled plastic in Oslo, Norway, under actual winter conditions to see if it can provide warmer shelter to aid refugees.

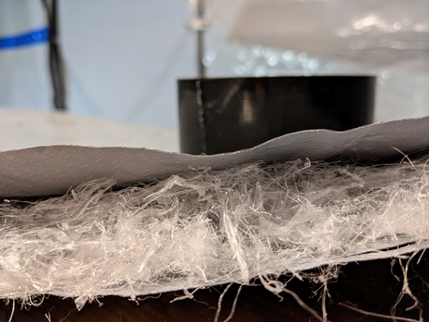

The insulation is created from recycled plastic by utilizing a technology called Polyfloss. Created by melting plastic garbage and extruding it into a mass of thin fibers that look like candy floss, Polyfloss can be packed like traditional insulation. If tests show that the Polyfloss-insulated tent panels are effective, their use could greatly improve life for hundreds of thousands - and maybe millions - of displaced people.

Current heating solutions for those living in refugee camps are costly and energy intensive; for warmth in winter, displaced people there must depend on distributed blankets, stoves and fuel. All are costly, ineffective in extreme cold and hard on the environment.

But Polyfloss is none of those things. Polyfloss machines can be deployed on-site, so insulation can be made cost-effectively where it’s needed. It can be made inexpensively from locally collected plastic, reducing waste and fuel use. And it can be packed, shaped and formed to trap air between its fibers to insulate; early tests in the U.K. showed Polyfloss was effective in colder temperatures.

If they prove effective at keeping tents warmer, the Polyfloss-insulated tent panels could also spur job creation for refugees. Collecting plastic refuse from around the camps, turning it into Polyfloss, making the insulated shelters and distributing them could present possible economic opportunities for displaced people.

Despite being slowed by the pandemic, the team is hewing close to its project timeline; as planned, team members are now field-testing a full-scale insulated shelter against a non-insulated shelter set up on the grounds of Oslo’s Technical Museum of Norway to assess real-life performance during actual winter conditions. The tents are the standard IFRC-issued geodesic tents, modified with added Polyfloss-insulated wall panels.

“We’re testing the first-round prototype now; the Polyfloss insulation is kind of like a down jacket, but instead of down the filling is Polyfloss, and instead of quilting outside (the material) is tarp,” said Catherine Hebson, a Field Ready engineer conducting the tests in Oslo along with other consortium members.

In addition to measuring interior tent temperatures with and without the Polyfloss insulation, Hebson and a member of Engineers Without Borders Norway have been gathering data firsthand - by spending hours lying in the tents themselves in Oslo’s current 30-degree (Fahrenheit) temperatures. Two Norwegian families are also volunteering as test subjects, spending several nights sleeping in the insulated tent to give feedback on its warmth.

Once team members analyze the insulation ‘s heat retention data, “there needs to be a lot of discussion about how these will be manufactured and how to best attach the insulated walls,” Hebson said. ‘We also need to examine what happens with conductivity, air circulation and ventilation with people in there.”

While testing the insulated wall panels, the group is also eying other potential uses for the Polyfloss insulation, Hebson said. “Eventually there may be a whole suite of insulated products,” she said, such as mattresses and floor panels to protect those sleeping on a tent’s floor.

Volunteers and the team’s intrepid testers will spend the next weeks continuing their human occupancy tests, Hebson said.

The team hopes to conclude the field tests in the next several weeks and analyze the data; afterward, they plan to conduct lab tests of the insulated product and secure certifications. If all goes well, the final product and its production design could commence this summer.

_edited.png)

Comments